Ecosystems on the Brink

Dr Riley Elliot’s Mission Beneath the Waves

Each year, thousands of visitors converge on Tairua and the wider Coromandel Peninsula to surf, fish and spend golden days enjoying the crystal-clear water. But for marine biologist Dr Riley Elliott, Tairua is more than paradise, it’s his home, laboratory, classroom and a constant reminder of how much we stand to lose as the area’s ecosystems teeter on the brink.

“I grew up here in Tairua,” he says. “It’s where I learned to swim, fish, dive and navigate boats. It’s where I first started making a living on the water, and it’s also where I began to realise that the ocean I loved was changing, and not for the better.”

Elliott, best known for his television persona, Shark Man, is an expert on the ocean’s most feared predator, the great white shark. While he seems unfazed diving with these specialised predators, his journey began like everyone else’s: with fear.

A lifelong surfer, Elliott admits sharks haunted his thoughts every time he paddled out. Instead of avoiding that fear, he confronted it. “The only way to know if you should be afraid of a shark,” he says, “is to meet one face to face.” That decision shaped his life. While studying zoology and marine science at university, he spent every spare moment underwater, first spearfishing, then diving, and eventually tagging sharks. Time in South Africa introduced him to the great white and convinced him not only to study sharks but to change how people feel about them.

“Sharks and especially the great white shark are the ocean’s most misunderstood residents,” he says. “They aren’t taught how to live; migration, hunting, and breeding is all hard-wired into their DNA. My mission is to decode these behaviours. Despite roaming the seas for 70 million years, great whites remain an enigma.”

Not long after Elliott returned to New Zealand, a fatal great white shark attack on a swimmer just a few kilometres from his home raised questions no one could answer. Why were the sharks there, and what were they doing? Elliott realised he was uniquely placed to find out. He began tagging great whites off the South Island, and this led to a major scientific discovery: a new nursery ground for great whites, filled with newborns and sub-adults. “It’s like finding the cradle of the next generation,” he explains. “If we understand where they grow up, we can protect them before it’s too late.”

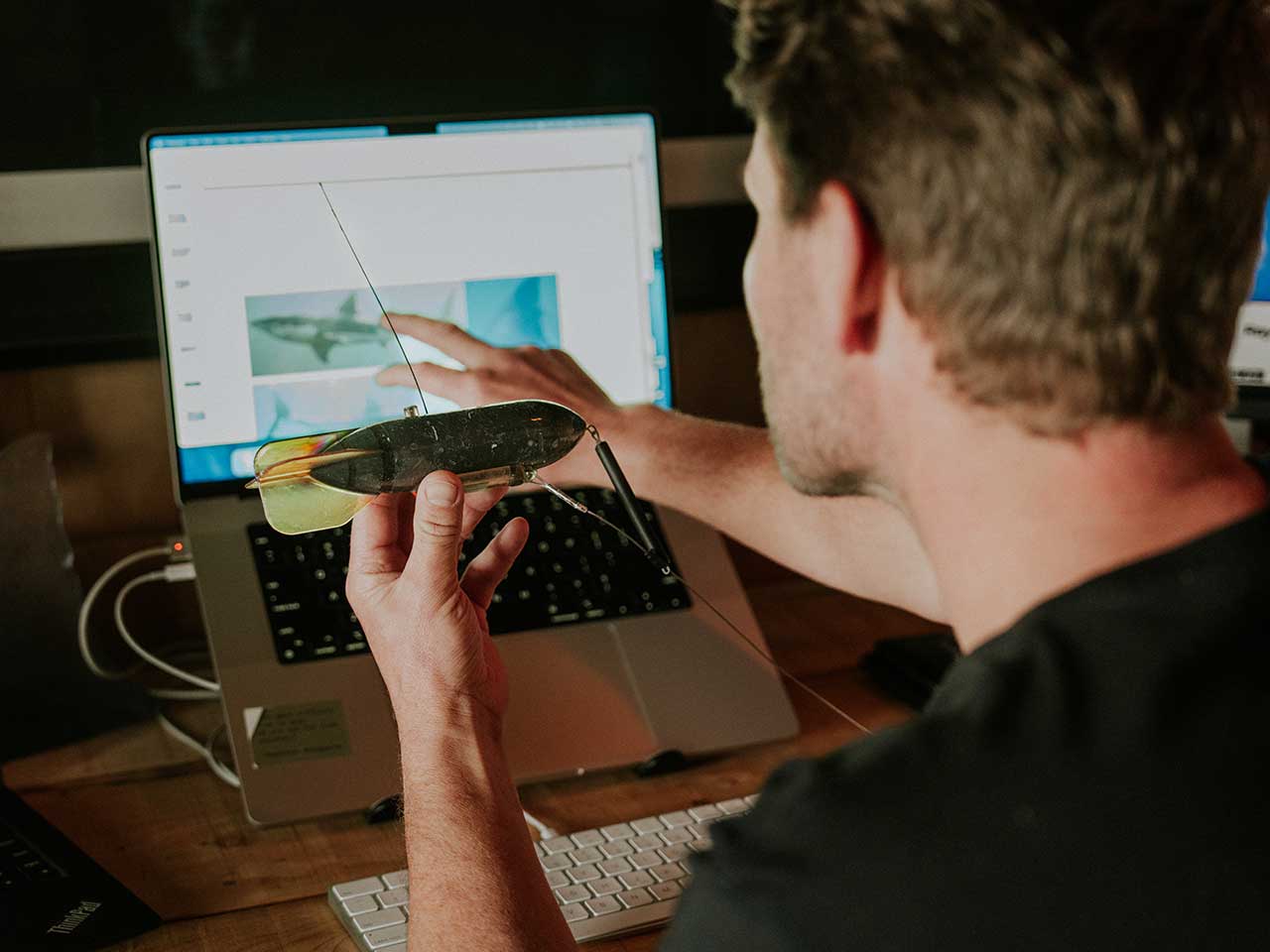

Elliot’s study tags selected sharks using a gentle, precise technique. A small dart is inserted at the base of the dorsal fin that causes no pain. Each time a tagged shark surfaces, a satellite pings its position, sending data to Elliott’s laptop and into the Great White App. This publicly available tracker turns research into shared discovery. “Every morning it’s like Christmas,” he laughs. “You wake up and check where your sharks have been overnight.”

The results have been astonishing. Some of the tagged juveniles have journeyed as far as Tonga, Fiji and New Caledonia, crossing oceans filled with fishing lines, trawl nets and plastic debris. “The app shows the gauntlet they run every day, and sometimes we see that they don’t make it back.”

Elliott also invites the public to name the sharks he tags, and this led to another insight. “I really thought the public would give them names like Slasher and Killer,” he says. “But instead, they’ve been called Bubbles, Happy, and Maureen. I guess that by giving a feared predator a gentle name, it reduces fear and creates a sense of connection that makes people more likely to care about its protection.”

It was while studying great whites and other sharks in the waters around New Zealand that Dr Elliott discovered something alarming. Despite New Zealand’s reputation for being clean and green, he was seeing another reality below the waves - depleted scallop beds, vanishing crayfish and silent bays where seabirds once plunged into swirling bait balls, all stark reminders of how much has been lost in a short time. “It’s confronting,” he says. “We’ve taken so much, so fast. But the ocean is forgiving if we give it time and help.”

That belief fuels his mission to shift public perception from fear to fascination. Through documentaries like Shark Man, Discovery’s Shark Week and his online following, Elliott turns complex science into stories that capture hearts as well as minds. “Science should excite and inspire,” he says. “If people connect emotionally, they start to care, and that’s when change happens.”

Elliott’s ‘excite and inspire’ approach has already paid dividends, helping to drive New Zealand’s ban on shark finning, saving an estimated 150,000 sharks a year. It has also contributed to the end of Western Australia’s shark culls. But Elliot knows the fight is only just beginning, and while people fear sharks, they are a crucial part of the ocean’s food web. “Sharks are the doctors and the clean-up crew of the sea,” he explains. “They keep populations healthy. Without them, the whole system collapses, right down to phytoplankton that gives us every second breath we take.”

Elliott’s passion for conservation has also become a family affair. His wife, Amber Jones, an accomplished marine photographer, captures his encounters behind the lens, and together they share their adventures and passion for conservation with their young daughter, Sailor —a fitting name for a child born into a family whose lives are guided by the water.

After three decades exploring his home coastline, Elliott often looks back on his progression from kayak to dinghy, then to a small tinny before graduating to the Yamaha-powered research vessel that carries him offshore. “Each boat opened another chapter of discovery,” he says. “You can’t understand the ocean by standing on the beach. You must get out there.”

On the ocean is where he’ll be found most days, charting shark migrations, collecting data and turning science into stories that inspire others to protect what remains. “Small, deliberate steps can ripple outward,” he explains. “A conversation that changes perception; a company choosing to invest in sustainability—these are all important ripples.” While he admits the trajectory we’re on is terrifying, the ocean can rebound if given the chance. “It’s not too late, but it is getting close,” he says.

For Yamaha Motor and Dr Riley Elliott, that chance begins with awareness—showing that science, storytelling and good partnerships can transform fear into fascination, and fascination into action. “If we protect the sharks, we protect the oceans. It’s as simple as that,” he says. “And if we protect the oceans, we protect ourselves.”

Elliott’s work demands stamina, passion, funding, and reliable equipment. It’s a combination that aligns with Yamaha’s Rightwaters initiative, a global program supporting projects that protect the marine environment. Through Yamaha Motor New Zealand, Rightwaters supplies the outboard power and technical support that keep Dr Elliott’s research moving. It’s a partnership based on shared values: responsibility, sustainability and respect for the water.

“Yamaha understands that the health of the ocean underpins everything,” Elliott explains. “Their support lets me reach remote areas and collect data that would otherwise be impossible. More importantly, it shows that industry and conservation can work together for the same outcome.”

“For Yamaha, backing Elliott is a tangible way to live its mission to preserve the resources we enjoy today so future generations can enjoy them tomorrow.

You can support Dr Riley Elliot's journey by following him on Instagram here or Facebook here. Alternatively you can learn more about the Great White app by clicking here.